The impacts of extreme rainfall could be more frequent and severe than had previously been thought at the last UN climate conference, COP25, two years ago in Madrid. A new generation of climate models and the latest IPCC assessment (AR6) have provided a new light to look at the recent catastrophic floods seen across the world in the last year and what could be expected in the future.

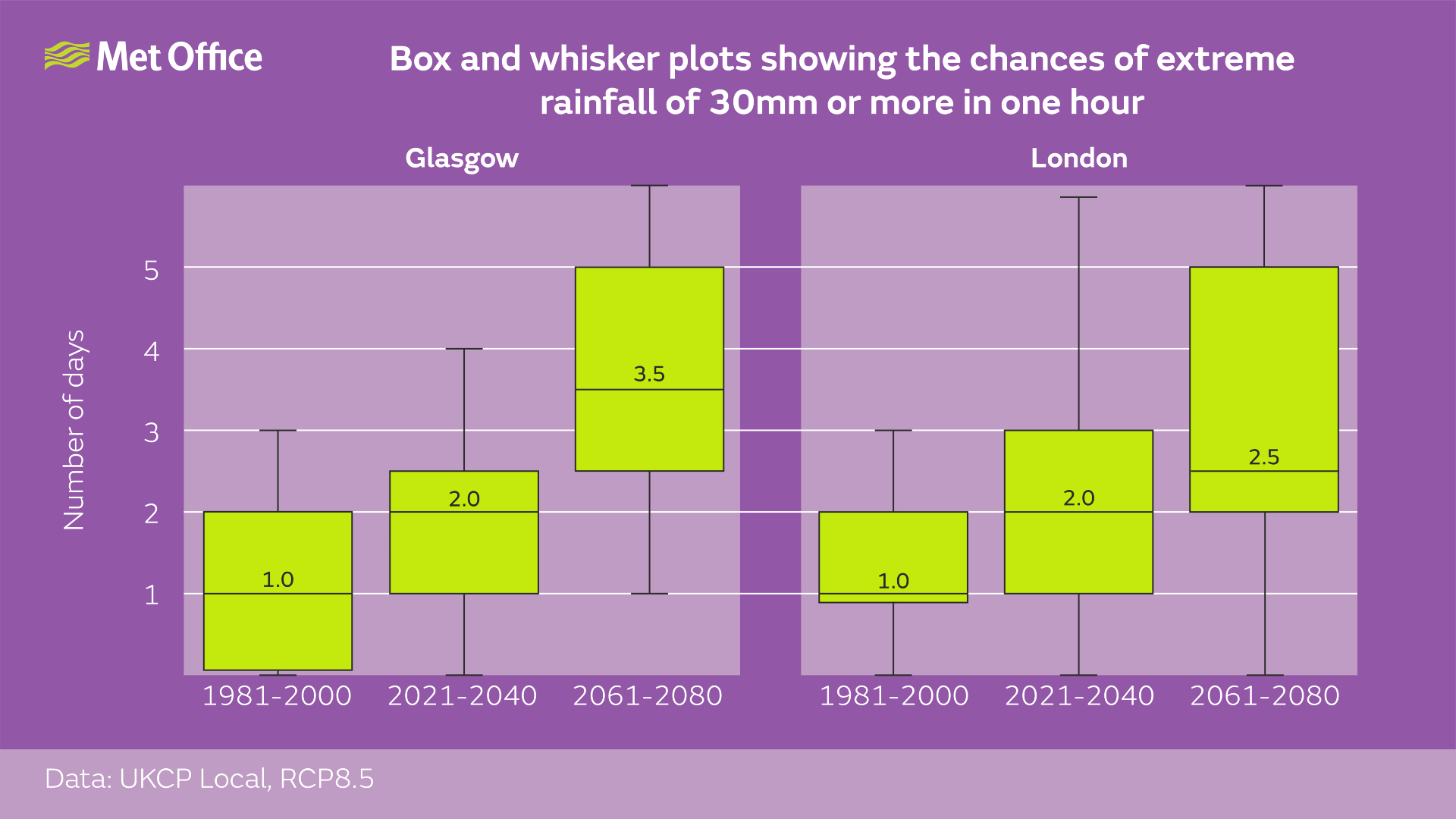

In a stark example, new calculations using a high emissions scenario with around 3°C of warming by 2070 show that in Glasgow, where COP26 is being hosted, the number of days where 30mm of rain or more is recorded in an hour could be 3.5 times more likely by the 2070s compared with the 1990s. In London 30mm/hr could be 2.5 times more likely. 30mm of rain in one hour is a threshold which is typically used to trigger flash flood warnings. These results suggest a big increase in the frequency of flash flood-producing rainfall events.

Although the high emissions scenario is higher than the expected outcome of COP26, plausible high emissions scenarios like this are routinely used for long term risk assessment. Recent flood events show that there is a greater urgency than had previously been thought about reducing emissions and preparing societies to make them more resilient to extreme rainfall events. These new climate projections are helping organisations and people improve their resilience to flooding.

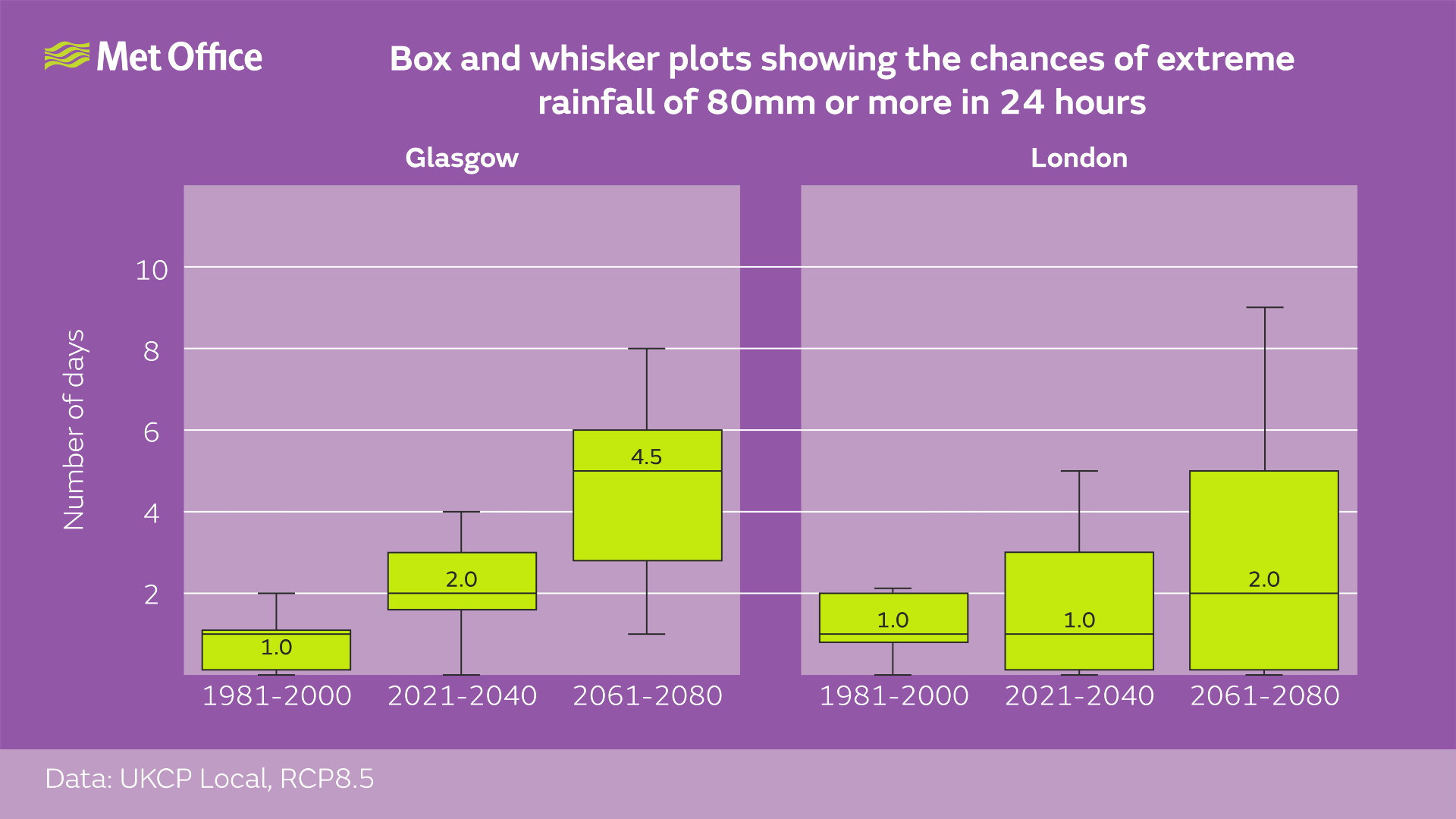

In addition to the increase in high intensity rainfall, the number of days when 80mm of rain falls in 24 hours could become 4.5 times more likely in Glasgow by 2070 under a high emissions scenario.

The calculations used the latest UKCP Local projections which were funded by BEIS and Defra. This is the first time national climate scenarios have been provided at a resolution on a par with weather forecast models. The UKCP Local projections provide new capability – allowing us to look at changes in local weather extremes over the coming decades.

Flooding events over the past 12 months include devastating flooding in central Europe during summer 2021, flooding of the London underground in July 2021 and in Zhengzhou, China in the same month. In the central Europe event, some parts of Western Europe received up to two months worth of rainfall in two days. A recent climate attribution study has shown that climate change made the one day rainfall in this region more intense – increasing the rainfall by between 3 and 19%.

In addition to increases in hourly rainfall intensity, the latest generation of high-resolution climate models also show more, slower-moving storms, which can lead to high rainfall accumulations, with high rainfall rates sustained over several hours. This has serious consequences for changing flood risk as was seen in central Europe in the summer. A recent study by Met Office and Newcastle University scientists showed that slow-moving storms with the potential for high rainfall accumulations are projected to be 14 times more frequent over land across Europe by 2100 under a high emissions scenario where global warming reaches 4.3°C.

Met Office climate scientist, Professor Lizzie Kendon, said: “Recent developments in high resolution climate projections are letting us examine changes in future extreme rainfall in unprecedented detail. We’re seeing that extreme rainfall events are being made both more frequent and more intense as a consequence of human induced climate change. Recent flooding events around the world show the devastation that intense rainfall can cause. By reducing our greenhouse gas emissions, the worst impacts can be avoided, but organisations and individuals need to be resilient to the changes in our weather that we’re already committed to”.

Because of the global warming that’s already taken place, rainfall extremes have already started to change. Science Fellow in Climate Attribution at the Met Office Hadley Centre, Professor Peter Stott, said: “Climate change is no longer just an issue about the future. With the atmosphere having already warmed by around 1°C it can hold roughly 7% more moisture than it would have in the pre-industrial period, leading to more extreme rainfall events. As well as the chances of more extreme rainfall in the future we’re seeing the influence of climate change on the weather we’re experiencing now.”

Extreme weather events are nothing new, but the frequency with which they are occurring is changing. For the UK, five of the 10 wettest years on record have happened since 2000, and the flooding in London in July 2021 is illustrative of the type of event we expect to increasingly see in future.

The science of climate change predictions is just the start of the process. To enable mitigation and adaption actions to be taken, we need to understand climate change impacts. For example, cities are particularly vulnerable to high intensity rainfall and work under the UK Climate Resilience programme is looking to better understand these risks.

With the new high resolution models providing data at a scale that can be directly fed into impacts models, partners in academia and government are able to use the latest UKCP projections as direct input into hydrological models, and hence understand the implications for flooding. This includes, for example, looking at risks for the urban drainage network.

A Met Office event at the COP26 Science Pavilion on Tuesday 9 November at 19:30 will see panellists discussing how this information can be better used in decision making. You can stream the event live on our Science and Services YouTube channel.ADVERTISEMENT