A lack of both archaeological and written sources for Herefordshire makes it difficult to discuss this topic in great detail. It is assumed that the Black Death affected this county in much the same way as it did many other parts of England (and indeed Europe), and that between one-third and one-half of the population died.

A report from the archaeological excavation carried out in Hereford Cathedral Close in 1993 describes a probable plague pit which would have contained the bodies of around 300 or 400 people:

“The Black Death is seen as the most probable cause and it appears from the way that the bodies were deposited in the pit that several were brought on carts and put in the pit at one time. This was borne out by thin layers of clay covering several bodies at a time. This would have given some protection against the stench of decaying bodies and was probably an attempt to ward off infection.” (Richard Stone and Nic Appleton-Fox, A View from Hereford’s Past, Logaston Press, 1996, pp. 24-25)

Without dating and examining the bones it is difficult to determine the date and cause of death.

The other archaeological pieces of evidence which are used to study the effects of the plague are the deserted medieval villages which dot our landscape. However, as mentioned in the Deserted Villages section, it is difficult to know why a settlement was abandoned unless there is corresponding documentary evidence.

Our best records here in Herefordshire are ecclesiastical ones (relating to churches and the cathedral). They do not give us a complete picture, nevertheless we can establish patterns of depopulation. The Bishop’s Register, for example, lists all new priests in a parish. It indicates that 56 priests died in 1349, compared to few than 10 in each of the other years between 1346 and 1352. (The Register of John de Trillek 1344-1361, edited by Joseph Henry Parry, 1910; there is a copy in the Herefordshire Record Office.)

Often the scribe fails to note the reason why there was a new priest in a parish, but even if we look only at the figures where the reason is given as death, the mortality rate for 1349 is staggering. There were so many new entries for 1349 that the scribe probably gave up on putting in the reason for the vacancy.

It would not be surprising if priests tried to charge more for their services, seeing that they were in such great demand. We know from sources outside the county that labourers too tried to increase their wages in the aftermath of the Black Death. The Bishop’s Register for 18th June 1349 noted that clergy were warned not to charge excessive fees on pain of excommunication (The Register of John de Trillek 1344-1361, p. 321).

Several churches in Herefordshire were joined together during this period, because the land could not support more than one priest and the plague had so depopulated the area. An example of this is the merger of Great and Little Collington in 1352, where there is also evidence of a deserted village.

In Aston, one of the Bishop of Worcester’s estates (which now is in Herefordshire) the reduction of tenants in the Black Death was 80%.

The Register of John Trillek, Bishop of Hereford records that in the four episcopal manors of Bosbury, Colwall, Coddington and Cradley as many as 158 tenants died of the plague. The terrible upheaval caused by these deaths was felt by the surviving population for years to come. The bishop received complaints in 1352 from his labourers that they feared for their lives and were kept from working by marauders and criminals (William J. Dohar, The Black Death and Pastoral Leadership: The Diocese of Hereford in the Fourteenth Century, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995, p. 38).

How was the city of Hereford affected? We have no population statistics available to us, but we do know that the market was moved to a point about a mile to the west of the city walls to prevent contamination. Mass burials were reported, and one parishioner remembered seeing up to 20 bodies buried from St. Peter’s Church in a single day (William J. Dohar, p. 39).

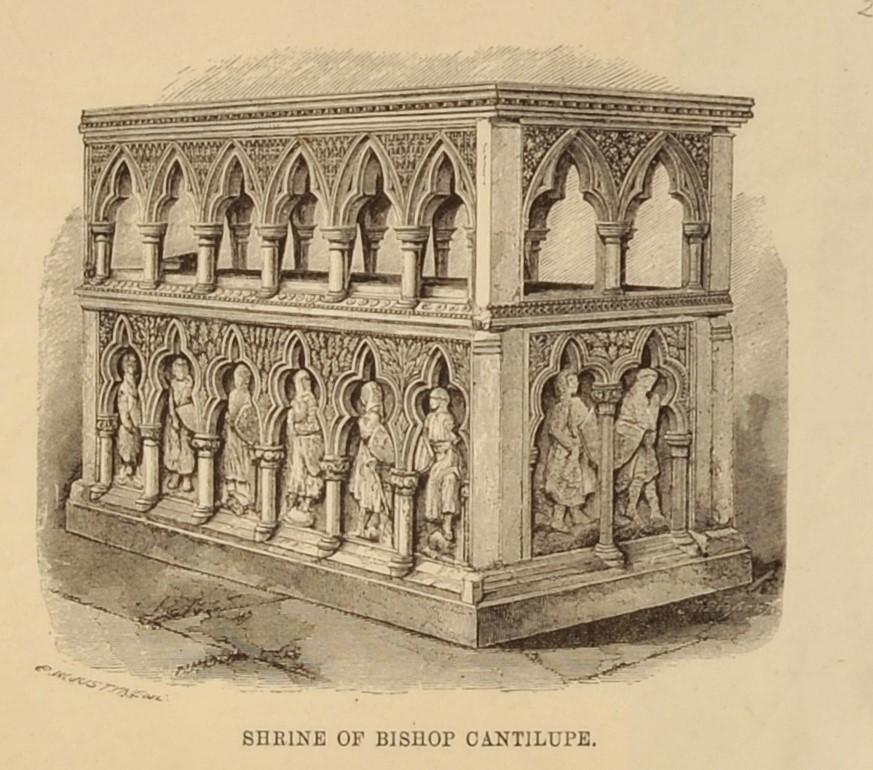

As we know, medieval doctors did not have a cure for the plague. What Hereford did have was a saint, namely St. Thomas Cantilupe, a former Bishop of Hereford who had been canonised (made a saint) in 1320. Many Christians believe that praying to a saint in times of need might bring them help. It is therefore not surprising that a magnificent shrine was placed in the Lady Chapel of the Cathedral and that the remains of St. Thomas were transferred there in a lavish ceremony in 1349, the year that the Black Death was stalking the county (G. Aylmer and J. Tiller (eds.), Hereford Cathedral: A History, 2000).

During this terrible time, the relics of St. Thomas (parts of his body or skeleton) were also carried through the streets in a religious procession in an attempt to ward off the Black Death. But the plague was very even-handed, and members of the clergy were as badly affected as the rest of the population.

One religious institution in the county suffered particularly badly. Flanesford Priory was founded only three years before the Black Death, and even though the house was probably meant to maintain thirteen canons, it never recovered and only ever supported two or three canons.

[Original author: Toria Forsyth-Moser, 2002-3]

You can read more at Herefordshire Through Time – https://htt.herefordshire.gov.uk/herefordshires-past/the-medieval-period/the-black-death/